PART 3/6

By 2007, American culture had reached a crescendo of spectacle, and a young Kim Kardashian, on the heels of a sex tape scandal, stood poised to engineer one of the most profitable image rehabilitations in modern history.

Once mocked as “famous for nothing,” the Kardashians now command a multibillion-dollar empire spanning fashion, beauty, wellness, gaming, and criminal justice reform. To dismiss her as superficial is to underestimate the totalizing structure she and her family have built.

As Christopher Lasch wrote in The Culture of Narcissism, “the contemporary climate is therapeutic, not religious. People today hunger not for personal salvation, but for the feeling, the momentary illusion, of personal well-being.” The Kardashians offer that illusion at scale, through beauty products, aspiration, and the constant illusion of companionship. And like the most enduring cults, it doesn’t feel like one at all.

“Money was always the goal, but I was obsessed with fame—like, embarrassingly obsessed.”

— Kim Kardashian's interview in Vogue Arabia, September 2019.

Their success cannot be separated from the rise of consumer narcissism, nor from the media’s role in constructing a new, surgically achievable beauty ideal. Reality programming like KUWTK significantly influences young women’s decisions to undergo cosmetic procedures, and in turn, has influenced cultural norms. Since 2000, cosmetic procedures have increased by approximately 115% overall, with a 24% rise in procedures among women under 30 between 2013 and 2018 alone.

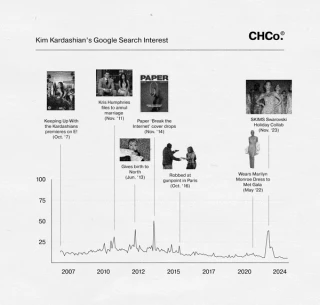

Whether revered or reviled, the Kardashians have occupied the center of American cultural fixation for nearly two decades. Their genius lies not in their appeal but in their inescapability.

This is largely because obsession is a more insidious form of control than belief. Theorists like Byung-Chul Han argue that modern domination is no longer top-down. It’s internalized.

In The Burnout Society, Byung-Chul Han argues that modern systems don’t force obedience; they get us to perform it ourselves. We expose our lives, emotions, and identities willingly, and that visibility becomes a form of control. Obsession, then, isn’t just passion; it’s self-surveillance. Roland Barthes might call this mythologization: the transformation of the banal into the sacred through repetition and symbolic weight.

The Kardashians operate within this logic. They don’t need to demand attention; we’ve been conditioned to give it freely.

As follows are the six structural pillars of cult control. Each one maps onto the mechanics of identity construction, emotional dependency, semantic control, and behavioral feedback.

Each of these is an independent unit of influence and a mutually reinforcing subsystem.

“In societies dominated by modern conditions of production, life is presented as an immense accumulation of spectacles.” — Guy Debord.

In the wake of the 2001 writers' strike and the post-dot-com advertising slump, networks turned to reality television as a low-cost, high-return solution. Unscripted formats required no unionized writers, minimal production budgets, and delivered massive viewer engagement. Early successes like Survivor (2000), Big Brother (2000), and American Idol (2002) proved the model: reality TV was scalable, addictive, and inexpensive to produce.

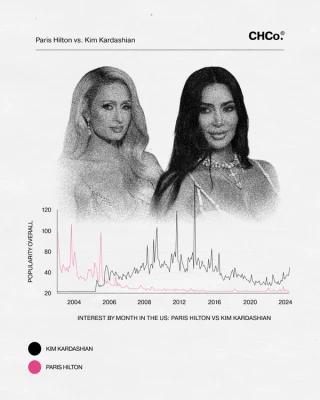

But more importantly, it offered something scripted formats couldn’t: the illusion of access. The Real World established the blueprint, but it was The Simple Life and Laguna Beach that revealed the commercial power of following people. By 2004, reality TV made up over 40% of primetime programming across major networks, and viewers were spending more than eight hours a month on unscripted content. Audiences, increasingly saturated with options, were less interested in plot development and more drawn to intimacy and recurring characters.

Kim Kardashian spent her early life in the shadows of other people’s scandals. Her father, Robert Kardashian, was a key figure on O.J. Simpson’s legal defense team, placing the family adjacent to one of the most sensationalized trials in American history. In the early 2000s, she worked as a stylist and assistant to Paris Hilton, quietly studying how tabloid culture, paparazzi infrastructure, and reality television could transform social capital into a marketable brand.

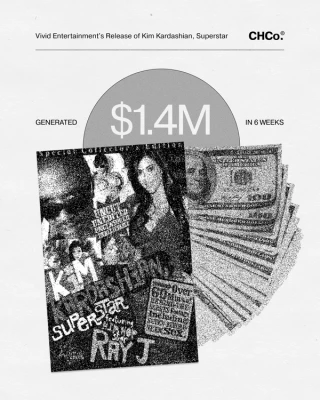

The sex tape Kim Kardashian, Superstar, filmed in 2003 with Ray J, was released by Vivid Entertainment in early 2007, reportedly generating over $1.4 million in its first six weeks. Kim filed a lawsuit against Vivid, claiming unauthorized release, but dropped it within months in what most reports suggest was a negotiated settlement that showcased the tape as a marketing catalyst. Ray J and others later confirmed Kris Jenner’s involvement in selecting the tape for distribution to maximize exposure.

Just months later, Keeping Up with the Kardashians premiered on E! in October 2007. According to The Hollywood Reporter, the show was essentially a long-form marketing tool for the family’s boutique, DASH, but it quickly evolved into the flagship reality franchise of the network.

What the Kardashians built through reality television wasn't traditional visibility, but a closed-loop system of references. Weddings, divorces, medical emergencies, product launches: all presented with equal narrative importance, merging into a continuous flow of events without clear hierarchy or resolution. Over time, the line between real-life documentation and scripted storytelling blurred and eventually disappeared.

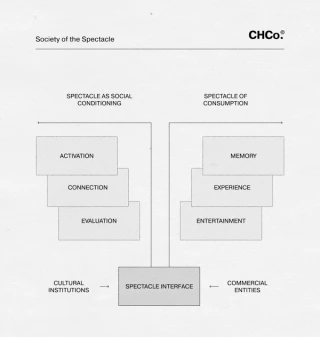

In this structure, obsession is created through constant repetition. Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle outlines how images start to replace real life, turning people into passive viewers instead of active participants. Audiences were conditioned not to follow a narrative but to maintain contact. To return. As Kardashian Kolloquium notes, Kim’s image no longer functions as a character but as an interface, a surface that delivers products, values, and cues.

“The viewer feels they know the figure on screen, while the figure remains entirely unaware of the viewer’s existence.” — Horton and Wohl.

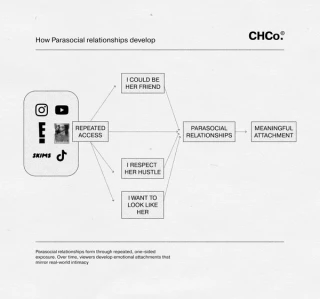

The term parasocial relationship was coined in 1956 by sociologists Donald Horton and Richard Wohl to describe the illusion of a face-to-face connection between a media consumer and a performer. Originally observed in the context of television hosts and radio personalities, these one-sided relationships mimic intimacy without reciprocity. The viewer feels they know the figure on screen, while the figure remains entirely unaware of the viewer’s existence.

In its earliest formulation, the parasocial dynamic was thought to stabilize audience loyalty through the illusion of accessibility. But what began as a passive psychological phenomenon has since evolved into an active strategy, particularly in digital environments where media figures can manufacture interaction, ritualize vulnerability, and simulate emotional availability at scale.

When social media entered the mainstream, Kardashian was one of the first to exploit its potential. In 2015, she sold over 30,000 copies of Selfish in its first week, a coffee table book composed entirely of selfies. It functioned as both self-parody and as a strategic asset, serving as an acknowledgement of her public image and a monetization of it. She was in on the joke and therefore capable of profiting from her audience’s obsession.

This strategy extended into SKKN and SKIMS, where Kardashian collapsed the distinction between persona and product. She shared tutorials, narrated product development, and posted campaign footage herself. The products remained the same, but the mode of engagement changed. You were not buying a beauty line or shapewear; you were buying Kim in as many forms as she could convince you to want.

By contrast, Jessica Simpson’s fashion empire, the first celebrity label to exceed $1 billion in annual revenue, relied heavily on wholesale deals and retail licensing. That model fundamentally lacked ongoing fan integration. When her parent company, Sequential Brands, filed for bankruptcy in 2021, Simpson was forced to repurchase her own brand for approximately $65 - 88 million despite earlier peak revenue. This underscores the structural difference: Kardashian embedded community and storytelling into her brand’s DNA, while Simpson’s brand, though long-running, remained externally managed and ultimately unsustainable without celebrity authorship.

In a 2011 analysis of Kardashian's Facebook activity, Jennifer Lueck found she wove product endorsements into personal stories, using emotional disclosure to deepen viewer connection, a strategy that increased positive engagement, especially among her female audience.

The relationship was dialogic. When SKIMS launched as “Kimono” and met cultural appropriation backlash, Kardashian responded publicly and changed the name. That response signaled something critical: she was listening. Fans felt part of the process, which deepened their investment. User-generated content became a continuation of the format she’d already modeled.

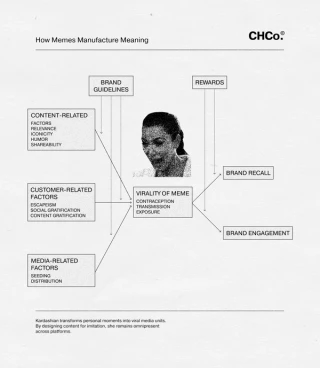

The term meme was introduced by evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins in The Selfish Gene (1976) to describe how cultural information spreads through imitation and replication. In digital culture, memes act as compressed carriers of collective meaning, optimized for circulation.

Kim Kardashian has weaponized this logic with precision. Her “ugly crying face,” first seen in Keeping Up with the Kardashians, became a viral reaction image, then licensed merchandise. Her 72-day marriage and subsequent divorce from Kris Humphries became a serialized media arc that sustained attention for multiple seasons. Rather than suppress scandal, she consistently transformed it into replicable media units, images, quotes, GIFs, that extended her reach across platforms.

As media theorist Limor Shifman notes, the most successful memes are simple, emotionally resonant, and endlessly adaptable. Kardashian’s image functions like modular code, easily copied, remixed, and repackaged without losing its meaning. In 2022 alone, over 1.6 million TikToks used audio from Kardashian clips, with “Don’t be f-ing rude!” becoming a recurring sound for creators reenacting drama. This allowed her to remain omnipresent, not by chasing relevance, but by engineering it into the participatory architecture of internet culture.

L. Ron Hubbard reframed personal failure as both narrative fuel and institutional proof. To suffer was to know, and to know was to lead. Kardashian follows a similar logic. Her scandals, sex tape, divorce, and internet mockery are not liabilities but initiation events. Each moment of public shame is rewritten as part of her story, used to show she’s in control. As Robert Jay Lifton writes in Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism, “the self must be surrendered before it can be transformed.”

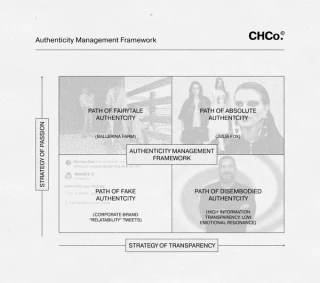

Lifton talks about two tools of control: confession and sacred truth. Confession makes someone seem honest and human. Sacred truth makes their beliefs feel untouchable. Kardashian uses both. Her posts about motherhood, trauma, burnout, and law school are part of the brand. Her values, like self-improvement or female resilience, aren’t framed as opinions. They’re styled as facts. And they’re backed by aesthetic, expert approval, and constant visibility. As Byung-Chul Han puts it, today’s internet runs on emotional exposure. Being seen has become a kind of labor. Kardashian stays visible to prove she’s still evolving, and to keep us watching.

Her law school pivot, for example, was framed as moral evolution. But it also justified new partnerships, from SKIMS maternity lines to criminal justice reform alliances. Each narrative of growth spawned new cycles of content and commerce. Authenticity, in this structure, is not an end state. It is a behavioral loop: reveal, reform, monetize.

Structurally, authenticity becomes a ritual of purification. The reveal functions like a public confession, which invites reciprocal vulnerability. Fans, in turn, disclose themselves, posting bodies in SKIMS, sharing insecurities, and participating in the aesthetics of transformation. In Han’s terms, the neoliberal subject becomes both worker and product.

“Kardashian’s ability to constantly adapt, rebrand and shift her persona… ensures she remains relevant across platforms and generations.” — Jennifer Lueck, 2015

Kardashian engineered feedback loops that outlived the platforms they were born on. The tabloid gave way to the tweet, the tweet to the TikTok, but the image remained. Her silhouette alone, contoured waist, large bust, and famous hips function as cultural shorthand. Like Warhol’s soup can or Monroe’s red lip, she has achieved a visual archetype. Her likeness is now part of the semiotic code of American consumerism.

In a media landscape governed by velocity, Kardashians offer continuity. Culture now moves at the speed of the feed, where relevance decays in hours. Yet her presence persists. To remain conversant in contemporary culture, to be fluent in its references, aesthetics, and values, one must pass through Kardashian’s orbit. She has become a marker of cultural literacy. Ignoring her is not neutral; it's a form of illiteracy, a kind of semiotic disconnection.

Even her quiet periods, time away from public scandal or press tours, are never absent. They are ambient. Her voice surfaces in a podcast. Her shapewear appears in a selfie. Her children trend on TikTok. Presence, at this stage, requires no performance.

Legacy here isn’t rooted in admiration but in recursion. Kardashian’s genius lies not in demanding attention, but in collapsing the boundary between attention and existence. To look away is to fall behind; to engage is to stay in sync with culture itself.

This is the logic of the most enduring cults: not conversion, but saturation. Like L. Ron Hubbard or David Berg, Kardashian built a cosmology, a belief system encoded in visuals, rituals, and language. You don’t have to believe in her to be shaped by her. To know her name is to participate in the larger cultural obsession.

Kim Kardashian’s cult leadership is not a product of accidental fame but of deliberate engineering. She absorbed ridicule and redeployed it as ritual. She trained her audience not to watch, but to participate, mimic, and evangelize. Her image scaled from tabloid fodder to archetype, while her influence outpaced the very platforms that delivered her. What began as visibility became ontology. Our cultural concept of Kim surpasses obsession. It is a belief system built through repetition, emotional entanglement, and participatory submission.

Academic & Theoretical Sources

Journal Articles & Media Studies

Media, News, and Interviews

Other Referenced Works